Yesterday should have been a triumphant reprieve from the hornswoggled state of the nation. The start of Black History Month began less than two weeks after Obama left office, and the examples the former first family set for our nation offered an uplifting counter-narrative to the systematic inequality and oppression that so much of this country still use to exploit and marginalize black Americans.

Part in parcel with our president’s threats of martial law on Chicago’s high-crime areas, his repeated past references to “the blacks”, and the fact that no police department or court has mandated any accountability for their repeated, disproportionate murder of unarmed black men and women, the lessons that February affords to folks of all colors about what it means to be a black in America are sorely needed right now.

Doing his part, Trump held a Black History Month “event”, described to all of of the black folks in attendance as “our little breakfast, our little get-together.” With cameras rolling, he name-dropped token cabinet pick Ben Carson before touting Carson’s heading of HUD using old stereotypes—”That’s a big job. That’s a job that’s not only housing, but it’s mind and spirit. Right, Ben?”

He then briefly praised Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. for a few seconds before condemning a Time reporter for misreporting that Trump had removed a bust of Dr. King from his office. What had begun as hollow generic praise of the civil rights hero soon turned into another condemnation of the media, ending with the words “a disgrace.”

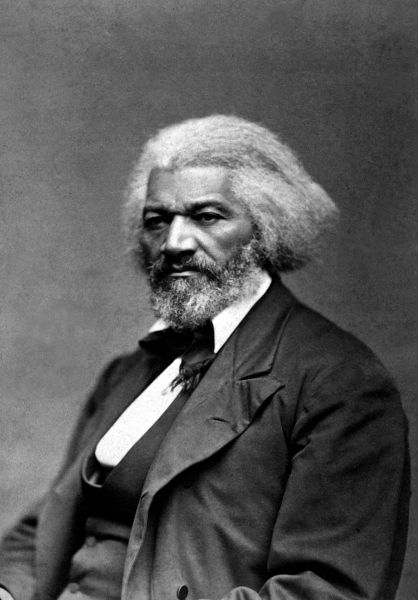

But the coup de grace came when Trump proved he had no knowledge of who Frederick Douglass was, a man who escaped slavery to become the national leader of the abolitionist movement.

“Frederick Douglass is an example of somebody who’s done an amazing job and is being recognized more and more, I noticed,” said Trump, effectively demonstrating that he had no idea who Frederick Douglass was with one sentence and reducing an American beacon of freedom to someone whose accomplishments were only valid with the approval of another white leader.

The condescending horrorshow was nothing new for people whose ancestors came here in shackles and chains, but there on national news, it bore before those with closed eyes just how little our country has changed in 250-plus years. The stunt also recalled how quickly Obama’s enormous contributions to this country were defaced by the new administration, a reminder that through all past peaceful transfers of power, no incoming president has gone to such lengths to tarnish and taint the prior leader’s legacy as our current president has tried to do to Obama’s.

And when working to understand how this cultural deception occurs, a look at the history of American music is telling through similar processes of condescending, capitalist swindling.

“It’s not just one or two songs—there’s a whole history of music that they’re trying to hide under the rug.”—George Clinton

Every uniquely American genre has roots in black culture, from rock ‘n’ roll, blues, gospel and folk to jazz, funk, hip-hop, R&B and even country music. From the time of slavery, when song provided a necessary a spiritual reprieve for the extreme working and living conditions of slaves, music has been at the core of black American identity, communicating a resolve and conviction that capitalist monied interests have long exploited, preying off the naiveté and industry ignorance of the artists who recorded their hearts and souls to acetate.

In R&B, Rhythm and Business: The Political Economy of Black Music, editor Norman Kelley identifies a point in the ’50s when this practice reached epidemic proportions, as a “usual pattern” of turnover for black groups saw acts like The Chords, The Spaniels, The Charms, The Spiders, The Four Tunes and The Crows chart in 1954 only to vanish into obscurity one year later:

“Often catapulted to success from a neighborhood street corner or, like Little Richard, from a bus terminal kitchen where he was washing dishes, black musicians seldom had access to good advice about record contracts, royalty payments, marketing, promotion, or career development. As a result, they were routinely swindled out of their publishing rights and underpaid for record sales.”

Kelley cites Saul Bihari, founder of an independent record label called Modern that included John Lee Hooker, Etta James, Lightin’ Hopkins and B.B. King on its roster, explaining how he wouldn’t pay his artists anything at all:

“We used to bring ’em in, give ’em a little bottle of booze and say, ‘Sing me a song about your girl’ or ‘Sing me a song about Christmas.’ They’d pluck around a little on their guitars and say ‘O.K.’ and make up a song as they went along. We’d give them a subject and off they’d go. When it came time to quit, we’d give them a wave that they had 10 seconds to finish.”

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SBgQezOF8kY&w=560&h=315]

Kelley then recalls an interesting story wherein Ahmet Ertegun, the former president of Atlantic, remembered meeting a Columbia representative during Atlantic’s early years:

“He wanted to make a deal whereby Columbia would distribute for Atlantic Records because we seemed to be very good at what he called ‘race records.’ So I said, ‘Well, what would you offer us?’ He said, ‘Three precent.’ ‘Three precent!’ I said, ‘We’re paying our artists more than that!’ And he said, ‘You’re paying those people royalties? You must be out of your mind!’ Of course he didn’t call them ‘people.’ He called them something else.”

These are all clear examples of exploiting talented young black artists without any context or knowledge of what’s fair in an industry, under the guise that all’s fair in race and capitalism. But it still continues to this day, more than half a century later.

Funk legend George Clinton spoke to me in 2015 about the endless litigation he’s undertaken in trying to win back his masters from Bridgeport Music, a company that owns the rights to 150-plus songs written by Clinton and other members of his bands. Bridgeport claims that Clinton signed over his rights to the music in 1982 and 1983, but Clinton claimed his signature was forged.

And as the P-Funk mothership hangs in the Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture, Clinton has worked tirelessly to clean up his legacy. “People don’t realize that there’s a federal investigation,” he told me. “It’s not just one or two songs—there’s a whole history of music that they’re trying to hide under the rug.”

Students of music history will know these predatory kinds of practices continued to hurt black artists long after Clinton, too. The story of N.W.A. and their manager Jerry Heller, as recently immortalized in the film Straight Outta Compton, tells Ice Cube’s side of the story, complete with a shiesty, walking Jewish stereotype in Heller, portrayed by Paul Giamiatti. Whether or not Heller defrauded the group as plainly as these past examples is unclear, although it fits the narrative.

Such reported swindling has done a lot of damage to the relationship between blacks and Jews, which I’ll explore next week through the lens of rapper Lupe Fiasco’s recent diatribe against Jews in the music industry. But it’s done a lot of damage to the cultural worth of our country, too, demonstrating another plain example of how our capitalist system routinely preys on the value and work that people of color and other vulnerable populations (women, immigrants, et al.) produce.

On SNL a few weeks ago, Leslie Jones asked why every month isn’t Black History Month, pointing out that relegating inclusivity and education about black culture to a lone month defeats the point of inclusivity all together.

When we look at how “separate but equal” the pantheon of American black music is kept from other music to this day, a similar truth materializes—that true inclusivity involves recognition of artists beyond racially stigmatized genre categories at The Grammys or separate entertainment channels. True inclusivity will take some reflection to realize that what we call American music and what we call black music are inherently one and the same.